| Autor: | Pauli Virtanen |

|---|

Numpy se encuentra en la base del montón de herramientas científicas de Python. Su propósito es simple: implementar operaciones eficientes sobre muchos items en un bloque de memoria. Entender detalladamente como funciona sirve de ayuda para poder hacer un uso más eficiente de su flexibilidad, usando útiles atajos y creando nuevo trabajo basado en él.

Este tutorial pretende cubrir:

Preerequisitos

En esta sección numpy será importado de la siguiente forma

>>> import numpy as np

Contenido

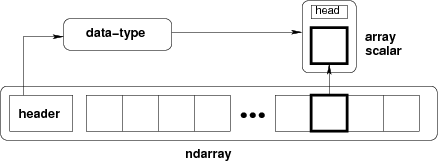

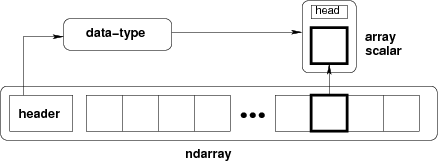

ndarray =

bloque de memoria + esquema de indexación + descriptor del tipo de dato

- Dato bruto (raw data)

- Cómo localizar un elemento

- Cómo interpretar un elemento

typedef struct PyArrayObject {

PyObject_HEAD

/* Block of memory */

char *data;

/* Data type descriptor */

PyArray_Descr *descr;

/* Indexing scheme */

int nd;

npy_intp *dimensions;

npy_intp *strides;

/* Other stuff */

PyObject *base;

int flags;

PyObject *weakreflist;

} PyArrayObject;

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.int32)

>>> x.data

<read-write buffer for ..., size 16, offset 0 at ...>

>>> str(x.data)

'\x01\x00\x00\x00\x02\x00\x00\x00\x03\x00\x00\x00\x04\x00\x00\x00'

Dirección en memoria de los datos:

>>> x.__array_interface__['data'][0]

64803824

Recordatorio: dos ndarrays deben compartir la misma memoria:

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

>>> y = x[:-1]

>>> x[0] = 9

>>> y

array([9, 2, 3])

La memoria no tiene que pertenecer a un ndarray:

>>> x = '1234'

>>> y = np.frombuffer(x, dtype=np.int8)

>>> y.data

<read-only buffer for ..., size 4, offset 0 at ...>

>>> y.base is x

True

>>> y.flags

C_CONTIGUOUS : True

F_CONTIGUOUS : True

OWNDATA : False

WRITEABLE : False

ALIGNED : True

UPDATEIFCOPY : False

Los flags owndata y writeable indican el estátus de la memoria.

dtype describe un único item en el array:

| type | scalar type de los datos, puede ser uno de: int8, int16, float64, et al. (tamaño fijo) str, unicode, void (tamaño flexible) |

| itemsize | tamaño del bloque de datos |

| byteorder | byte order: big-endian > / little-endian < / not applicable | |

| fields | sub-dtypes, si es un tipo de datos estructurados |

| shape | forma del array, si es un sub-array |

>>> np.dtype(int).type

<type 'numpy.int64'>

>>> np.dtype(int).itemsize

8

>>> np.dtype(int).byteorder

'='

El cabecero del fichero .wav:

| chunk_id | "RIFF" |

| chunk_size | 4-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| format | "WAVE" |

| fmt_id | "fmt " |

| fmt_size | 4-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| audio_fmt | 2-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| num_channels | 2-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| sample_rate | 4-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| byte_rate | 4-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| block_align | 2-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| bits_per_sample | 2-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

| data_id | "data" |

| data_size | 4-byte unsigned little-endian integer |

El cabecero del fichero .wav como un tipo de datos estructurados Numpy:

>>> wav_header_dtype = np.dtype([

... ("chunk_id", (str, 4)), # flexible-sized scalar type, item size 4

... ("chunk_size", "<u4"), # little-endian unsigned 32-bit integer

... ("format", "S4"), # 4-byte string

... ("fmt_id", "S4"),

... ("fmt_size", "<u4"),

... ("audio_fmt", "<u2"), #

... ("num_channels", "<u2"), # .. more of the same ...

... ("sample_rate", "<u4"), #

... ("byte_rate", "<u4"),

... ("block_align", "<u2"),

... ("bits_per_sample", "<u2"),

... ("data_id", ("S1", (2, 2))), # sub-array, just for fun!

... ("data_size", "u4"),

... #

... # the sound data itself cannot be represented here:

... # it does not have a fixed size

... ])

Ver también

wavreader.py

>>> wav_header_dtype['format']

dtype('|S4')

>>> wav_header_dtype.fields

<dictproxy object at ...>

>>> wav_header_dtype.fields['format']

(dtype('|S4'), 8)

Ejercicio

Mini-ejercicio, hacer un dtype “disperso” usando offsets y solo algunos de los campos:

>>> wav_header_dtype = np.dtype(dict(

... names=['format', 'sample_rate', 'data_id'],

... offsets=[offset_1, offset_2, offset_3], # counted from start of structure in bytes

... formats=list of dtypes for each of the fields,

... ))

y usar eso para leer la tasa de muestreo (sample rate) y data_id (como sub-array).

>>> f = open('data/test.wav', 'r')

>>> wav_header = np.fromfile(f, dtype=wav_header_dtype, count=1)

>>> f.close()

>>> print(wav_header)

[ ('RIFF', 17402L, 'WAVE', 'fmt ', 16L, 1, 1, 16000L, 32000L, 2, 16, [['d', 'a'], ['t', 'a']], 17366L)]

>>> wav_header['sample_rate']

array([16000], dtype=uint32)

Vamos a intentar acceder al sub-array:

>>> wav_header['data_id']

array([[['d', 'a'],

['t', 'a']]],

dtype='|S1')

>>> wav_header.shape

(1,)

>>> wav_header['data_id'].shape

(1, 2, 2)

¡Cuando accedemos a sub-arrays las dimensiones se añaden al final!

Nota

Existen módulos como wavfile, audiolab, etc. para leer datos de sonido...

casting (o transformación de tipo)

- al asignar

- en la construcción de arrays

- en aritmética

- etc.

- y manualmente: .astype(dtype)

re-interpretación de dato

- manualmente: .view(dtype)

Casting en aritmética, resumiendo:

Casting en copias generales de datos:

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.float)

>>> x

array([ 1., 2., 3., 4.])

>>> y = x.astype(np.int8)

>>> y

array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=int8)

>>> y + 1

array([2, 3, 4, 5], dtype=int8)

>>> y + 256

array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=int8)

>>> y + 256.0

array([ 257., 258., 259., 260.])

>>> y + np.array([256], dtype=np.int32)

array([257, 258, 259, 260], dtype=int32)

Casting en setitem: dtype del array no cambia al asignar al item:

>>> y[:] = y + 1.5

>>> y

array([2, 3, 4, 5], dtype=int8)

Nota

Para conocer las reglas exactas: ver la documentación: http://docs.scipy.org/doc/numpy/reference/ufuncs.html#casting-rules

Bloques de datos en memoria (4 bytes)

| 0x01 | || | 0x02 | || | 0x03 | || | 0x04 |

¿Cómo cambiar de uno a otro?

Cambiando el dtype:

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.uint8)

>>> x.dtype = "<i2"

>>> x

array([ 513, 1027], dtype=int16)

>>> 0x0201, 0x0403

(513, 1027)

0x01 0x02 || 0x03 0x04 Nota

little-endian: el byte menos significativo se encuentra a la izquierda en memoria

Creando una nueva vista:

>>> y = x.view("<i4")

>>> y

array([67305985], dtype=int32)

>>> 0x04030201

67305985

0x01 0x02 0x03 0x04

Nota

.view() crea vistas, no copia (o altera) el bloque de memoria

solo cambia el dtype (y ajusta la forma del array):

>>> x[1] = 5

>>> y

array([328193], dtype=int32)

>>> y.base is x

True

Mini-ejercicio: re-interpretación de datos

Ver también

view-colors.py

Tenemos datos RGBA en un array:

>>> x = np.zeros((10, 10, 4), dtype=np.int8)

>>> x[:, :, 0] = 1

>>> x[:, :, 1] = 2

>>> x[:, :, 2] = 3

>>> x[:, :, 3] = 4

donde la tercera dimensión indica cada uno de los canales R, B, and G y alpha.

¿Cómo hacer un array estructurado (10, 10) con los field names ‘r’, ‘g’, ‘b’, ‘a’ sin crear una copia de los datos?

>>> y = ...

>>> assert (y['r'] == 1).all()

>>> assert (y['g'] == 2).all()

>>> assert (y['b'] == 3).all()

>>> assert (y['a'] == 4).all()

Solución

Advertencia

Otro array tomando, exactamente, 4 bytes de memoria:

>>> y = np.array([[1, 3], [2, 4]], dtype=np.uint8).transpose()

>>> x = y.copy()

>>> x

array([[1, 2],

[3, 4]], dtype=uint8)

>>> y

array([[1, 2],

[3, 4]], dtype=uint8)

>>> x.view(np.int16)

array([[ 513],

[1027]], dtype=int16)

>>> 0x0201, 0x0403

(513, 1027)

>>> y.view(np.int16)

array([[ 769, 1026]], dtype=int16)

>>> 0x0301, 0x0402

(769, 1026)

La pregunta

>>> x = np.array([[1, 2, 3], ... [4, 5, 6], ... [7, 8, 9]], dtype=np.int8) >>> str(x.data) '\x01\x02\x03\x04\x05\x06\x07\x08\t'¿En qué byte en x.data commienza el item x[1,2]?

La respuesta (en Numpy)

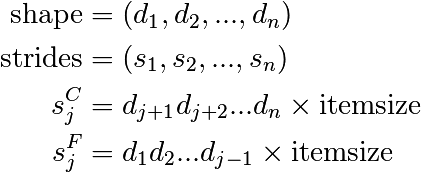

- strides (o pasos): El número de bytes a saltar para encontrar el siguiente elemento

- 1 stride por dimensión

>>> x.strides (3, 1) >>> byte_offset = 3*1 + 1*2 # to find x[1,2] >>> x.data[byte_offset] '\x06' >>> x[1, 2] 6

- simple, flexible

>>> x = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

... [4, 5, 6],

... [7, 8, 9]], dtype=np.int16, order='C')

>>> x.strides

(6, 2)

>>> str(x.data)

'\x01\x00\x02\x00\x03\x00\x04\x00\x05\x00\x06\x00\x07\x00\x08\x00\t\x00'

>>> y = np.array(x, order='F')

>>> y.strides

(2, 6)

>>> str(y.data)

'\x01\x00\x04\x00\x07\x00\x02\x00\x05\x00\x08\x00\x03\x00\x06\x00\t\x00'

De forma similar para dimensiones mayores:

Nota

Ahora podemos entender el comportamiento de .view():

>>> y = np.array([[1, 3], [2, 4]], dtype=np.uint8).transpose()

>>> x = y.copy()

La transposición no afecta al layout de memoria de los datos, solo a los strides

>>> x.strides

(2, 1)

>>> y.strides

(1, 2)

>>> str(x.data)

'\x01\x02\x03\x04'

>>> str(y.data)

'\x01\x03\x02\x04'

Nota

NdT: Slicing, traducido literalmente, significa rebanada, rodaja. Con este término nos referimos a tomar una porción/rodaja/rebanada de los datos, es decir, usar un subconjunto de los datos disponibles en el array

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], dtype=np.int32)

>>> y = x[::-1]

>>> y

array([6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1], dtype=int32)

>>> y.strides

(-4,)

>>> y = x[2:]

>>> y.__array_interface__['data'][0] - x.__array_interface__['data'][0]

8

>>> x = np.zeros((10, 10, 10), dtype=np.float)

>>> x.strides

(800, 80, 8)

>>> x[::2,::3,::4].strides

(1600, 240, 32)

Stride manipulation

>>> from numpy.lib.stride_tricks import as_strided

>>> help(as_strided)

as_strided(x, shape=None, strides=None)

Make an ndarray from the given array with the given shape and strides

Advertencia

as_strided does not check that you stay inside the memory block bounds...

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.int16)

>>> as_strided(x, strides=(2*2, ), shape=(2, ))

array([1, 3], dtype=int16)

>>> x[::2]

array([1, 3], dtype=int16)

Ver también

stride-fakedims.py

Exercise

array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.int8) -> array([[1, 2, 3, 4], [1, 2, 3, 4], [1, 2, 3, 4]], dtype=np.int8)using only as_strided.:

Hint: byte_offset = stride[0]*index[0] + stride[1]*index[1] + ...

Spoiler

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.int16)

>>> x2 = as_strided(x, strides=(0, 1*2), shape=(3, 4))

>>> x2

array([[1, 2, 3, 4],

[1, 2, 3, 4],

[1, 2, 3, 4]], dtype=int16)

>>> y = np.array([5, 6, 7], dtype=np.int16)

>>> y2 = as_strided(y, strides=(1*2, 0), shape=(3, 4))

>>> y2

array([[5, 5, 5, 5],

[6, 6, 6, 6],

[7, 7, 7, 7]], dtype=int16)

>>> x2 * y2

array([[ 5, 10, 15, 20],

[ 6, 12, 18, 24],

[ 7, 14, 21, 28]], dtype=int16)

... seems somehow familiar ...

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=np.int16)

>>> y = np.array([5, 6, 7], dtype=np.int16)

>>> x[np.newaxis,:] * y[:,np.newaxis]

array([[ 5, 10, 15, 20],

[ 6, 12, 18, 24],

[ 7, 14, 21, 28]], dtype=int16)

Ver también

stride-diagonals.py

Challenge

Pick diagonal entries of the matrix: (assume C memory order):

>>> x = np.array([[1, 2, 3], ... [4, 5, 6], ... [7, 8, 9]], dtype=np.int32) >>> x_diag = as_strided(x, shape=(3,), strides=(???,))Pick the first super-diagonal entries [2, 6].

And the sub-diagonals?

- (Hint to the last two: slicing first moves the point where striding

- starts from.)

Solution

Ver también

stride-diagonals.py

Challenge

Compute the tensor trace:

>>> x = np.arange(5*5*5*5).reshape(5,5,5,5) >>> s = 0 >>> for i in xrange(5): ... for j in xrange(5): ... s += x[j,i,j,i]by striding, and using sum() on the result.

>>> y = as_strided(x, shape=(5, 5), strides=(TODO, TODO)) >>> s2 = ... >>> assert s == s2

Solution

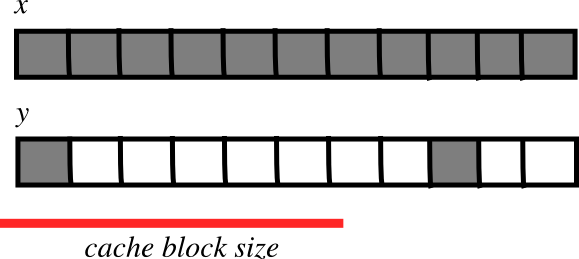

Memory layout can affect performance:

In [1]: x = np.zeros((20000,))

In [2]: y = np.zeros((20000*67,))[::67]

In [3]: x.shape, y.shape

((20000,), (20000,))

In [4]: %timeit x.sum()

100000 loops, best of 3: 0.180 ms per loop

In [5]: %timeit y.sum()

100000 loops, best of 3: 2.34 ms per loop

In [6]: x.strides, y.strides

((8,), (536,))

Smaller strides are faster?

fewer transfers needed

fewer transfers needed faster

fasterVer también

numexpr is designed to mitigate cache effects in array computing.

Sometimes,

>>> a -= b

is not the same as

>>> a -= b.copy()

>>> x = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

>>> x -= x.transpose()

>>> x

array([[ 0, -1],

[ 4, 0]])

>>> y = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

>>> y -= y.T.copy()

>>> y

array([[ 0, -1],

[ 1, 0]])

Ufunc performs and elementwise operation on all elements of an array.

Examples:

np.add, np.subtract, scipy.special.*, ...

Automatically support: broadcasting, casting, ...

The author of an ufunc only has to supply the elementwise operation, Numpy takes care of the rest.

The elementwise operation needs to be implemented in C (or, e.g., Cython)

Provided by user

void ufunc_loop(void **args, int *dimensions, int *steps, void *data)

{

/*

* int8 output = elementwise_function(int8 input_1, int8 input_2)

*

* This function must compute the ufunc for many values at once,

* in the way shown below.

*/

char *input_1 = (char*)args[0];

char *input_2 = (char*)args[1];

char *output = (char*)args[2];

int i;

for (i = 0; i < dimensions[0]; ++i) {

*output = elementwise_function(*input_1, *input_2);

input_1 += steps[0];

input_2 += steps[1];

output += steps[2];

}

}

The Numpy part, built by

char types[3]

types[0] = NPY_BYTE /* type of first input arg */

types[1] = NPY_BYTE /* type of second input arg */

types[2] = NPY_BYTE /* type of third input arg */

PyObject *python_ufunc = PyUFunc_FromFuncAndData(

ufunc_loop,

NULL,

types,

1, /* ntypes */

2, /* num_inputs */

1, /* num_outputs */

identity_element,

name,

docstring,

unused)

ufunc_loop is of very generic form, and Numpy provides pre-made ones

| PyUfunc_f_f | float elementwise_func(float input_1) |

| PyUfunc_ff_f | float elementwise_func(float input_1, float input_2) |

| PyUfunc_d_d | double elementwise_func(double input_1) |

| PyUfunc_dd_d | double elementwise_func(double input_1, double input_2) |

| PyUfunc_D_D | elementwise_func(npy_cdouble *input, npy_cdouble* output) |

| PyUfunc_DD_D | elementwise_func(npy_cdouble *in1, npy_cdouble *in2, npy_cdouble* out) |

The Mandelbrot fractal is defined by the iteration

where  is a complex number. This iteration is

repeated – if

is a complex number. This iteration is

repeated – if  stays finite no matter how long the iteration

runs,

stays finite no matter how long the iteration

runs,  belongs to the Mandelbrot set.

belongs to the Mandelbrot set.

Make ufunc called mandel(z0, c) that computes:

z = z0

for k in range(iterations):

z = z*z + c

say, 100 iterations or until z.real**2 + z.imag**2 > 1000. Use it to determine which c are in the Mandelbrot set.

Our function is a simple one, so make use of the PyUFunc_* helpers.

Write it in Cython

Ver también

mandel.pyx, mandelplot.py

Reminder: some pre-made Ufunc loops:

| PyUfunc_f_f | float elementwise_func(float input_1) |

| PyUfunc_ff_f | float elementwise_func(float input_1, float input_2) |

| PyUfunc_d_d | double elementwise_func(double input_1) |

| PyUfunc_dd_d | double elementwise_func(double input_1, double input_2) |

| PyUfunc_D_D | elementwise_func(complex_double *input, complex_double* output) |

| PyUfunc_DD_D | elementwise_func(complex_double *in1, complex_double *in2, complex_double* out) |

Type codes:

NPY_BOOL, NPY_BYTE, NPY_UBYTE, NPY_SHORT, NPY_USHORT, NPY_INT, NPY_UINT,

NPY_LONG, NPY_ULONG, NPY_LONGLONG, NPY_ULONGLONG, NPY_FLOAT, NPY_DOUBLE,

NPY_LONGDOUBLE, NPY_CFLOAT, NPY_CDOUBLE, NPY_CLONGDOUBLE, NPY_DATETIME,

NPY_TIMEDELTA, NPY_OBJECT, NPY_STRING, NPY_UNICODE, NPY_VOID

# The elementwise function

# ------------------------

cdef void mandel_single_point(double complex *z_in,

double complex *c_in,

double complex *z_out) nogil:

#

# The Mandelbrot iteration

#

#

# Some points of note:

#

# - It's *NOT* allowed to call any Python functions here.

#

# The Ufunc loop runs with the Python Global Interpreter Lock released.

# Hence, the ``nogil``.

#

# - And so all local variables must be declared with ``cdef``

#

# - Note also that this function receives *pointers* to the data;

# the "traditional" solution to passing complex variables around

#

cdef double complex z = z_in[0]

cdef double complex c = c_in[0]

cdef int k # the integer we use in the for loop

# Straightforward iteration

for k in range(100):

z = z*z + c

if z.real**2 + z.imag**2 > 1000:

break

# Return the answer for this point

z_out[0] = z

# Boilerplate Cython definitions

#

# You don't really need to read this part, it just pulls in

# stuff from the Numpy C headers.

# ----------------------------------------------------------

cdef extern from "numpy/arrayobject.h":

void import_array()

ctypedef int npy_intp

cdef enum NPY_TYPES:

NPY_CDOUBLE

cdef extern from "numpy/ufuncobject.h":

void import_ufunc()

ctypedef void (*PyUFuncGenericFunction)(char**, npy_intp*, npy_intp*, void*)

object PyUFunc_FromFuncAndData(PyUFuncGenericFunction* func, void** data,

char* types, int ntypes, int nin, int nout,

int identity, char* name, char* doc, int c)

void PyUFunc_DD_D(char**, npy_intp*, npy_intp*, void*)

# Required module initialization

# ------------------------------

import_array()

import_ufunc()

# The actual ufunc declaration

# ----------------------------

cdef PyUFuncGenericFunction loop_func[1]

cdef char input_output_types[3]

cdef void *elementwise_funcs[1]

loop_func[0] = PyUFunc_DD_D

input_output_types[0] = NPY_CDOUBLE

input_output_types[1] = NPY_CDOUBLE

input_output_types[2] = NPY_CDOUBLE

elementwise_funcs[0] = <void*>mandel_single_point

mandel = PyUFunc_FromFuncAndData(

loop_func,

elementwise_funcs,

input_output_types,

1, # number of supported input types

2, # number of input args

1, # number of output args

0, # `identity` element, never mind this

"mandel", # function name

"mandel(z, c) -> computes iterated z*z + c", # docstring

0 # unused

)

import numpy as np

import mandel

x = np.linspace(-1.7, 0.6, 1000)

y = np.linspace(-1.4, 1.4, 1000)

c = x[None,:] + 1j*y[:,None]

z = mandel.mandel(c, c)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.imshow(abs(z)**2 < 1000, extent=[-1.7, 0.6, -1.4, 1.4])

plt.gray()

plt.show()

Nota

Most of the boilerplate could be automated by these Cython modules:

Several accepted input types

E.g. supporting both single- and double-precision versions

cdef void mandel_single_point(double complex *z_in,

double complex *c_in,

double complex *z_out) nogil:

...

cdef void mandel_single_point_singleprec(float complex *z_in,

float complex *c_in,

float complex *z_out) nogil:

...

cdef PyUFuncGenericFunction loop_funcs[2]

cdef char input_output_types[3*2]

cdef void *elementwise_funcs[1*2]

loop_funcs[0] = PyUFunc_DD_D

input_output_types[0] = NPY_CDOUBLE

input_output_types[1] = NPY_CDOUBLE

input_output_types[2] = NPY_CDOUBLE

elementwise_funcs[0] = <void*>mandel_single_point

loop_funcs[1] = PyUFunc_FF_F

input_output_types[3] = NPY_CFLOAT

input_output_types[4] = NPY_CFLOAT

input_output_types[5] = NPY_CFLOAT

elementwise_funcs[1] = <void*>mandel_single_point_singleprec

mandel = PyUFunc_FromFuncAndData(

loop_func,

elementwise_funcs,

input_output_types,

2, # number of supported input types <----------------

2, # number of input args

1, # number of output args

0, # `identity` element, never mind this

"mandel", # function name

"mandel(z, c) -> computes iterated z*z + c", # docstring

0 # unused

)

ufunc

output = elementwise_function(input)

Both output and input can be a single array element only.

generalized ufunc

output and input can be arrays with a fixed number of dimensions

For example, matrix trace (sum of diag elements):

input shape = (n, n) output shape = () i.e. scalar (n, n) -> ()Matrix product:

input_1 shape = (m, n) input_2 shape = (n, p) output shape = (m, p) (m, n), (n, p) -> (m, p)

- This is called the “signature” of the generalized ufunc

- The dimensions on which the g-ufunc acts, are “core dimensions”

Status in Numpy

>>> import numpy.core.umath_tests as ut

>>> ut.matrix_multiply.signature

'(m,n),(n,p)->(m,p)'

>>> x = np.ones((10, 2, 4))

>>> y = np.ones((10, 4, 5))

>>> ut.matrix_multiply(x, y).shape

(10, 2, 5)

Generalized ufunc loop

Matrix multiplication (m,n),(n,p) -> (m,p)

void gufunc_loop(void **args, int *dimensions, int *steps, void *data)

{

char *input_1 = (char*)args[0]; /* these are as previously */

char *input_2 = (char*)args[1];

char *output = (char*)args[2];

int input_1_stride_m = steps[3]; /* strides for the core dimensions */

int input_1_stride_n = steps[4]; /* are added after the non-core */

int input_2_strides_n = steps[5]; /* steps */

int input_2_strides_p = steps[6];

int output_strides_n = steps[7];

int output_strides_p = steps[8];

int m = dimension[1]; /* core dimensions are added after */

int n = dimension[2]; /* the main dimension; order as in */

int p = dimension[3]; /* signature */

int i;

for (i = 0; i < dimensions[0]; ++i) {

matmul_for_strided_matrices(input_1, input_2, output,

strides for each array...);

input_1 += steps[0];

input_2 += steps[1];

output += steps[2];

}

}

Suppose you

Currently, 3 solutions:

Mini-exercise using PIL (Python Imaging Library):

Ver también

pilbuffer.py

>>> import Image

>>> data = np.zeros((200, 200, 4), dtype=np.int8)

>>> data[:, :] = [255, 0, 0, 255] # Red

>>> # In PIL, RGBA images consist of 32-bit integers whose bytes are [RR,GG,BB,AA]

>>> data = data.view(np.int32).squeeze()

>>> img = Image.frombuffer("RGBA", (200, 200), data)

>>> img.save('test.png')

Q:

Check what happens if data is now modified, and img saved again.

import numpy as np

import Image

# Let's make a sample image, RGBA format

x = np.zeros((200, 200, 4), dtype=np.int8)

x[:,:,0] = 254 # red

x[:,:,3] = 255 # opaque

data = x.view(np.int32) # Check that you understand why this is OK!

img = Image.frombuffer("RGBA", (200, 200), data)

img.save('test.png')

#

# Modify the original data, and save again.

#

# It turns out that PIL, which knows next to nothing about Numpy,

# happily shares the same data.

#

x[:,:,1] = 254

img.save('test2.png')

Ver también

Documentation: http://docs.scipy.org/doc/numpy/reference/arrays.interface.html

>>> x = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

>>> x.__array_interface__

{'data': (171694552, False), # memory address of data, is readonly?

'descr': [('', '<i4')], # data type descriptor

'typestr': '<i4', # same, in another form

'strides': None, # strides; or None if in C-order

'shape': (2, 2),

'version': 3,

}

>>> import Image

>>> img = Image.open('data/test.png')

>>> img.__array_interface__

{'data': ...,

'shape': (200, 200, 4),

'typestr': '|u1'}

>>> x = np.asarray(img)

>>> x.shape

(200, 200, 4)

>>> x.dtype

dtype('uint8')

Nota

A more C-friendly variant of the array interface is also defined.

>>> x = np.array(['a', ' bbb', ' ccc']).view(np.chararray)

>>> x.lstrip(' ')

chararray(['a', 'bbb', 'ccc'],

dtype='|S5')

>>> x.upper()

chararray(['A', ' BBB', ' CCC'],

dtype='|S5')

Nota

.view() has a second meaning: it can make an ndarray an instance of a specialized ndarray subclass

Masked arrays are arrays that may have missing or invalid entries.

For example, suppose we have an array where the fourth entry is invalid:

>>> x = np.array([1, 2, 3, -99, 5])

One way to describe this is to create a masked array:

>>> mx = np.ma.masked_array(x, mask=[0, 0, 0, 1, 0])

>>> mx

masked_array(data = [1 2 3 -- 5],

mask = [False False False True False],

fill_value = 999999)

Masked mean ignores masked data:

>>> mx.mean()

2.75

>>> np.mean(mx)

2.75

Advertencia

Not all Numpy functions respect masks, for instance np.dot, so check the return types.

The masked_array returns a view to the original array:

>>> mx[1] = 9

>>> x

array([ 1, 9, 3, -99, 5])

You can modify the mask by assigning:

>>> mx[1] = np.ma.masked

>>> mx

masked_array(data = [1 -- 3 -- 5],

mask = [False True False True False],

fill_value = 999999)

The mask is cleared on assignment:

>>> mx[1] = 9

>>> mx

masked_array(data = [1 9 3 -- 5],

mask = [False False False True False],

fill_value = 999999)

The mask is also available directly:

>>> mx.mask

array([False, False, False, True, False], dtype=bool)

The masked entries can be filled with a given value to get an usual array back:

>>> x2 = mx.filled(-1)

>>> x2

array([ 1, 9, 3, -1, 5])

The mask can also be cleared:

>>> mx.mask = np.ma.nomask

>>> mx

masked_array(data = [1 9 3 -99 5],

mask = [False False False False False],

fill_value = 999999)

The masked array package also contains domain-aware functions:

>>> np.ma.log(np.array([1, 2, -1, -2, 3, -5]))

masked_array(data = [0.0 0.69314718056 -- -- 1.09861228867 --],

mask = [False False True True False True],

fill_value = 1e+20)

Nota

Streamlined and more seamless support for dealing with missing data in arrays is making its way into Numpy 1.7. Stay tuned!

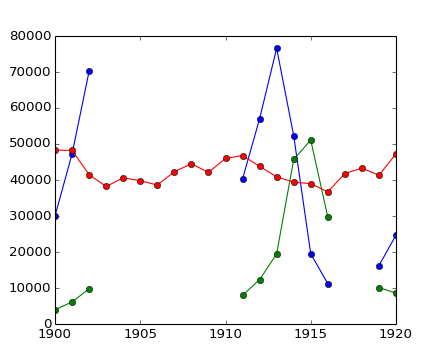

Example: Masked statistics

Canadian rangers were distracted when counting hares and lynxes in 1903-1910 and 1917-1918, and got the numbers are wrong. (Carrot farmers stayed alert, though.) Compute the mean populations over time, ignoring the invalid numbers.

>>> data = np.loadtxt('data/populations.txt')

>>> populations = np.ma.masked_array(data[:,1:])

>>> year = data[:, 0]

>>> bad_years = (((year >= 1903) & (year <= 1910))

... | ((year >= 1917) & (year <= 1918)))

>>> # '&' means 'and' and '|' means 'or'

>>> populations[bad_years, 0] = np.ma.masked

>>> populations[bad_years, 1] = np.ma.masked

>>> populations.mean(axis=0)

masked_array(data = [40472.7272727 18627.2727273 42400.0],

mask = [False False False],

fill_value = 1e+20)

>>> populations.std(axis=0)

masked_array(data = [21087.656489 15625.7998142 3322.50622558],

mask = [False False False],

fill_value = 1e+20)

Note that Matplotlib knows about masked arrays:

>>> plt.plot(year, populations, 'o-')

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at ...>, ...]

[source code, hires.png, pdf]

>>> arr = np.array([('a', 1), ('b', 2)], dtype=[('x', 'S1'), ('y', int)])

>>> arr2 = arr.view(np.recarray)

>>> arr2.x

chararray(['a', 'b'],

dtype='|S1')

>>> arr2.y

array([1, 2])

>>> np.matrix([[1, 0], [0, 1]]) * np.matrix([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

matrix([[1, 2],

[3, 4]])

Get this tutorial: http://www.euroscipy.org/talk/882

Title: numpy.random.permutations fails for non-integer arguments

I'm trying to generate random permutations, using numpy.random.permutations

When calling numpy.random.permutation with non-integer arguments

it fails with a cryptic error message::

>>> np.random.permutation(12)

array([ 6, 11, 4, 10, 2, 8, 1, 7, 9, 3, 0, 5])

>>> np.random.permutation(12.)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "mtrand.pyx", line 3311, in mtrand.RandomState.permutation

File "mtrand.pyx", line 3254, in mtrand.RandomState.shuffle

TypeError: len() of unsized object

This also happens with long arguments, and so

np.random.permutation(X.shape[0]) where X is an array fails on 64

bit windows (where shape is a tuple of longs).

It would be great if it could cast to integer or at least raise a

proper error for non-integer types.

I'm using Numpy 1.4.1, built from the official tarball, on Windows

64 with Visual studio 2008, on Python.org 64-bit Python.

What are you trying to do?

Small code snippet reproducing the bug (if possible)

Platform (Windows / Linux / OSX, 32/64 bits, x86/PPC, ...)

Version of Numpy/Scipy

>>> print np.__version__

2...

Check that the following is what you expect

>>> print np.__file__

/...

In case you have old/broken Numpy installations lying around.

If unsure, try to remove existing Numpy installations, and reinstall...

Documentation editor

Registration

Register an account

Subscribe to scipy-dev mailing list (subscribers-only)

Problem with mailing lists: you get mail

But: you can turn mail delivery off

“change your subscription options”, at the bottom of

Send a mail @ scipy-dev mailing list; ask for activation:

To: scipy-dev@scipy.org

Hi,

I'd like to edit Numpy/Scipy docstrings. My account is XXXXX

Cheers,

N. N.

- Check the style guide:

- http://docs.scipy.org/numpy/

- Don’t be intimidated; to fix a small thing, just fix it

- Edit

Edit sources and send patches (as for bugs)

Complain on the mailing list

Ask on mailing list, if unsure where it should go

Write a patch, add an enhancement ticket on the bug tracket

OR, create a Git branch implementing the feature + add enhancement ticket.

# Clone numpy repository

git clone --origin svn http://projects.scipy.org/git/numpy.git numpy

cd numpy

# Create a feature branch

git checkout -b name-of-my-feature-branch svn/trunk

<edit stuff>

git commit -a

git remote add github git@github:YOURUSERNAME/YOURREPOSITORYNAME.git

git push github name-of-my-feature-branch

Bug fixes always welcome!

Documentation work

API docs: improvements to docstrings

User guide

Needs to be done eventually.

Want to think? Come up with a Table of Contents

Ask on communication channels: